Ponce de León, Valladolid, arrived in the New World in 1502 together with the new governor of the Indies Nicolás de Ovando. He was forty-one years old and had participated in the guerra de Granada. He was of noble ancestry and was a page in the Court of Fernando el Católico.

During his first years in the New World he suffocated the indigenous rebellions on the Hispaniola being appointed governor of the Higüey. It was here that he heard about the alleged riches of Borinquén. Island located only eighty kilometers east of Hispaniola. He therefore applied for permission to explore it and was granted in 1508.

Governor Ovando’s orders were clear:

1º – To win the friendship of the island’s chieftains, for which reason he would not be able to use the natives in his service, nor take them to hunt, nor even disturb them.

2º – Establish their own tillage so that the settlers could support themselves.

3º – To erect a fortress that guarantees the security of all the Castilians.

4º – Locate gold mines and exploit them.

As we see more than a capitulation in which the governorship was handed over to Ponce de León, they were instructions of what the objectives were and how to act. Ovando did not want any more trouble or rebellions, and this was due to respect for the native. But as we shall see, things did not happen like this.

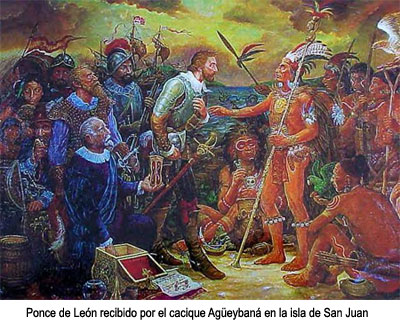

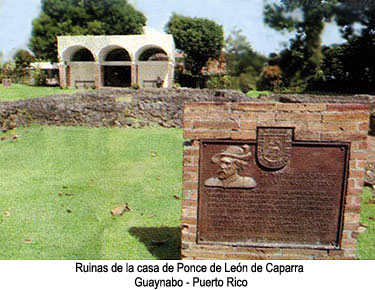

Ponce de León arrived with his men and founded the city of Caparra, the first European settlement in Puerto Rico, close to the current San Juan. He was warmly welcomed by the island’s chief cacique, Agüeybaná, who according to the chroniclers believed that the Spaniards had divine origins. As was customary when arriving to any region, the chieftain was asked about the places where gold could be found and this led them to two rivers, the Manatuabón and the Cebuco, where they found interesting amounts of the desired mineral.

Ponce quickly returned to Santo Domingo with the evidence collected and obtained the governorship of the island by instituting the regime of the commission already known in Spanish for which the natives had to work and pay tribute in exchange for receiving education and protection.

As expected, the natives could not put up with this situation very much and problems and rebellions began, as in the Hispaniola island. Agüeybaná had been very condescending to the Spaniards, actively collaborating with them but after his death his nephew, Agüeybaná II, much more bellicose and courageous than his uncle, who rose up in the Taína rebellion of 1511 and united a large part of the Chiefs who did not want to continue with the new situation.

Ponce de Leon’s response was not long in coming, he searched for, captured and executed all the rebel chieftains, crushing the Taino rebellion. Some natives managed to flee to the mountains, joining the Caribbean, to continue harassing the Europeans from there.